|

|

|

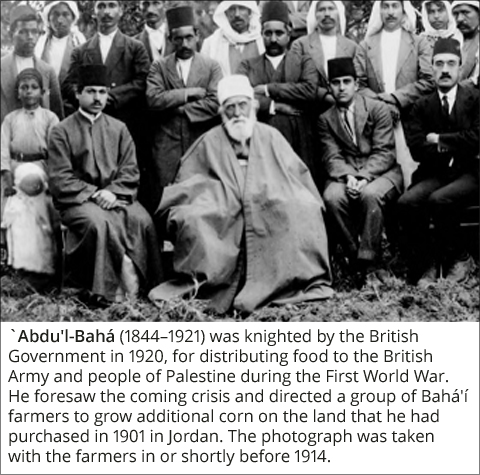

October 1, 2020 SEEDING SUSTAINABILITY  For the last decade of the 19th and the first two of the 20th century, the community founded by Bahá’u’lláh (an Arabic title meaning “glory of God”) was guided by his son Abbás. Bahá’u’lláh referred to this eldest son and successor as “the Master”, a recognition of his exemplary character; meanwhile, Abbás refused this and many other honorary titles in favour of ’Abdu’l-Bahá (servant of glory, servant of Bahá’u’lláh). His astounding life, embracing both humble service and enlightened leadership, was featured on September 11, the 8th episode of the local “ Big Ideas ” series. Paul Hanley, a writer and agriculture expert from Saskatoon, returned for a virtual presentation titled “’Abdu’l-Bahá: The Master of Social Action and Public Discourse.” How did this comparatively unknown figure – one who illuminates all of Bahá’í history and community development – exemplify Bahá’u’lláh’s call not just for reform but for global transformation? The Bahá’í approach to the renewal of society has three main elements: first, capacity-building at the grassroots; and where such development has progressed, undertaking societal improvement, plus contributing to ennobled conversation within those societies. The Bahá’í community has considered ‘Abdu’l-Bahá its Exemplar for nearly 130 years, and Hanley offered new insights into how his example continues to inspire. Consider that the Master was “an incredibly prolific writer”, with over 30,000 letters of guidance and encouragement to friends from both East and West, as well as several books. After decades of exile and imprisonment, he gave hundreds of public talks explicating his father’s principles. Meanwhile, he so transformed minds and hearts in his final place of banishment – the Turkish empire’s penal colony in what is now Akká, Israel – that he went from being a pariah – plotted against and despised – to acclaim by Palestinian Arabs as “the Lord of Generosity”, another title he refused to use. In 1921, 10,000 mourners accompanied his casket to its resting place on the side of Mount Carmel. “Oh, by the way,” Hanley chuckled, “he also headed a world religion for 30 years!” The heart of Hanley’s

discussion was a little-known project in

Adassiyah, a small village in Jordan. After the fall of the Turkish

empire freed him, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá purchased nearly 1,000 hectares of

parched, unpromising land. He envisioned a model agricultural

community. Initial plantings of grain and barley – often raided by

unfriendly neighbours – were supplemented not only by the cultivation

of fruit trees and vegetables, but also measures to improve the

conditions of the peasant farmers of the area. This pioneering example

of “just, productive and sustainable rural development” resulted in

Adassiyah becoming the Jordanian government’s “poster child” of

agricultural progress. |

|

|