|

|

|

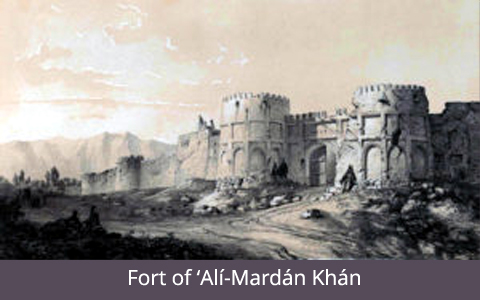

PART NINE October 27, 2019 THE GREAT DIVIDE The spark that set the city of Zanján aflame with persecution and great suffering was a small one: a simple quarrel between a Bábí youth and a Muslim youth. The Bábí youth was imprisoned by the governor, the Madju’d Dawlih – a maternal uncle of the new Sháh who was looking for ways to win the good graces of the sovereign. All efforts to have the boy released proved futile until Hujjat, a native of Zanján, stepped in to secure his release.  Hujjat was an early convert to the Bábí Faith. Originally a fiery cleric named Mullá Muhammad-‘Alí from Zanján, he had unorthodox ideas and often lamented how far the Shí’i religion had fallen. When the Báb’s star began to rise over the horizon of Persia, he sent his disciple Mullá Iskandar to Shíraz to conduct a minute and independent inquiry. When Mullá Iskandar – who had been deeply touched by the Báb – returned while Hujjat was entertaining a number of leading divines and announced that “whatever should be the verdict of his master, the same would he deem it his obligation to be,” Mullá Muhammad-‘Alí exploded in fury. “What! But for the presence of this distinguished company, I would have chastised you severely. How dare you consider matters of belief to be dependent upon the approbation or rejection of others!” When he then read the first line of the Qayyumu’l-Asma’, he fell to the ground and acknowledged that those words came from God and pledged his allegiance to the Báb, exhorting the gathering to follow suit, stating that “Whoso denies Him, him will I regard as the repudiator of God Himself.” In honour of his eloquent sermons and capacity to silence his detractors, the Báb called him Hujjat’ul-Islám, the Proof of Islám, and thereafter, Hujjat, a man who did not to live by half-measures, bravely taught the Bábí Faith with fire and passion. As a result, he was both hounded and hunted and forced to flee many a town and village. Eventually, he returned home and soon found himself in the midst of the crisis that had engulfed the Bábí community of Zanján. Incensed by the youth’s incarceration, Hujjat appealed to the governor to release the child and allow his father to be imprisoned instead, to no avail. A sum of money was also offered by the believers, but that too was ignored. Finally, Hujjat sent one of his comrades to meet with the governor and have the youth released. This man not only managed to free the youth and infuriate the governor, it inflamed the clergy of Zanján, who pressured the governor to arrest Hujjat. Although he sent guards to apprehend him, they were routed by a group of Bábís seeking to protect Hujjat, who, crying out Ya Sahibu’s Zaman!, O Lord of the Age!, wounded one of them and sent the others running in panic. This shout spread terror among the townspeople, and the guards, having failed to arrest Hujjat, instead arrested an unarmed Bábí who was then butchered by the governor, his attendants and even a Muslim cleric who stabbed him in the heart with a penknife. This murder aroused the bloodlust of many government officials who vowed to destroy the Bábí community with the approval of the governor, who agreed, sending a town crier out into the streets of Zanján to proclaim that whoever was willing to endanger his life, to forfeit his property and expose his wife and children to misery and shame, should throw in his lot with Hujjat and his companions, and that those who were desirous of ensuring the wellbeing and honour of themselves and their families, should withdraw from the neighbourhood in which the Bábís lived and seek the shelter of the sovereign’s protection. The town was immediately divided in two. It also divided families and caused great turmoil in many a home. That day, every tie of affection seemed to be dissolving, and solemn pledges were forsaken in favor of a loyalty mightier and more sacred than any earthly allegiance. As a result of this polarization, the Bábís took shelter at the turreted Fort of ‘Alí-Mardán Khán, where they built 28 barricades as a means of protecting themselves and from which they defended their battered community. The fortress housed some 2,000 Bábí men and 3,000 women and children, who also assisted in helping in whatever way they could. The women would sew, wash, cook, tend to the sick and wounded, gather cannonballs and bullets for reuse and cheered the warriors who sought to protect them. Some 200 joyful marriages took place in the fort presided by Hujjat, although no one knew if their spouse would survive the day.

|

|

|